Friday, April 4, 2014

The Last Templar, Michael Jecks

Michael Jecks' The Last Templar (1995), the first in a series of "Medieval West Country Mysteries", fails so spectacularly on so many levels, from simple word choice to characterization to plotting, that it seems as if Jecks had never written a novel before. In fact, it seems as if Jecks had never read a mystery novel before.

Why then did someone publish it? Who would publish thirty one others, the latest as recently as two thousand and thirteen?

No daggers out of four, and I'm pretty sure Jecks owes me a dagger for actually finishing the book.

Monday, March 24, 2014

Swan Song, Edmund Crispin

Gervase Fen makes his 4th appearance in Edmund Crispin's Swan Song (1947), which proves to be as much of a romantic comedy as a murder mystery, though Fen does solve an ingenious mystery.

Barzun and Taylor's A Catalogue of Crime (1971) says:

Educated at Merchant Taylors' and St. John's, Oxford, Edmund Crispin is a man of letters and a musician (organist and composer) as well as one of the masters of modern detective fiction since his 22nd year. Reserved in manner, but a charming conversationalist and as witty in life as he is in his books. His true career is in music, by which he lives as well as courts fame [as Bruce Montgomery]. His preferred composer is Brahms. His first detective novel, The Case of the Guilded Fly (1944), was written in fourteen days. Like those to follow, it features an Oxford professor of English literature, Gervase Fen, who is not at all donnish.A production of Wagner's Die Meistersinger provides Swan Song's setting and gives Crispin a chance to draw on his musical background.

A good example is this throwaway line on the Oxford Opera House, "About it are ranged busts of the greater operatic masters -- Wagner, Verdi, Mozart, Gluck, Mussorgsky. There is also one of Brahms -- for no very clear reason, though it may perhaps be a tribute to his curious and fortunately abortive project for an opera about gold-mining in the Yukon."

World War II had only just ended when Swan Song first came out and so this quote, from the producer of the opera in the book, carried much more of a sting: "When the Nazis came I was too old for their ideas, and I hated that such fools should worship the Meister, I had preferred that they banned his performances. So I worked here, and then there was the war, and fools said, 'Because Hitler is fond of Wagner we will not have Wagner in England.' Hitler was also fond of your Edgar Wallace, with his stories of violence, but no one said that they were not to be read."

Crispin slips in a comment on British post-WWII austerity as an character explains that she had been "In America. Playing Boheme and dying of consumption five times weekly. As a matter of fact, I nearly died of overeating. You should go to America, Adam. They have food there."

The best thing about Swan Song, though, remains our hero, Fen:

The significance of these recurrent utterances had at last penetrated to Fen's understanding. He became irresponsible.And Crispin is not adverse to a little slapstick when necessary:

"There's a diamond tiara gone," he said sternly. "And the specification of the atomic bomb. So if we're all reduced to molecular dust before we have time to turn round it will all be your fault."

"Oh, sir," said the chambermaid. "You're 'aving me on."

"You just wait and see," said Fen, wagging his forefinger at her, "you just wait and see if I'm having you on or not."

"Now, Lily Christine [Fen's car]," he muttered, "you can do something for your living."For this reader, Swan Song ended all too soon.

In this, unfortunately, he proved to be over-optimistic. Nothing he could contrive would start the car. He tampered with the levers, and wound the handle, until he was exhausted. Finally, in an access of vengeful fury, he hurled an empty petrol-can at the chromium nude on the radiator-cap, seized his wife's bicycle, and wobbled frantically away on it.

Three and seven-eights daggers our of four.

Thursday, March 20, 2014

The G-String Murders, Gypsy Rose Lee

When The G-String Murders (1941) hit the bookstore shelves, Gypsy Rose Lee, then only 28 years old, shined as the brightest start in burlesque. The book promised not only a titillating look backstage but also an exciting murder mystery.

As Sherrill Tippins explains in February House (2005), "Lee decided to "write a murder mystery set in the world of burlesque.... The murder weapon would be a chorus girl's G-string. She would call the book The G-String Murders. She was sure it would make a fortune and enhance her reputation as an "intellectual stripper" -- if she could only get it written."

Karen Abbott in American Rose: A Nation Laid Bare, the Life and Time of Gypsy Rose Lee (2010) points out that in 1940 Lee moved into 7 Middagh Street in New York city "with some of the most important writers and artists of the time: Carson McCullers, W.H. Auden, Benjamin Britten, Peter Pears, Chester Kallman, and George Davis, the openly gay fiction editor of Harper's Bazaar and an old friend -- the only one who knew her before she became Gypsy Rose Lee."

Tippins says:

Lee read the stack of murder mysteries that [her editor Lee] Wright recommended, met with Craig Rice, a Chicago beat reporter and best-selling female mystery writer who soon became a close friend, and bought herself a new typewriter ("I thought the blue ribbon was sexy"). Then she got back to work.

The trouble was, Gypsy didn't know how to write a novel.... [She hired] Dorothy Wheelock to write a first draft. But Gypsy found that no matter how hard Dorothy worked, the material failed to satisfy her. It was obvious to the younger writer -- and finally clear to Gypsy as well -- that calling herself an author wasn't enough. She wanted to write the book as well.

George suggested that Gypsy begin by simply dictating some of her favorite stories to him. As she talked, he typed her words on [an] old typewriter....

After much discussion, they decided to approach the book like a jigsaw puzzle: first write down all of Gypsy's anecdotes, character descriptions, and entertaining burlesque details, then arrange them into a rough story line.Unfortunately, Lee's lack of familiarity with the genre makes for a pretty dull mystery with an overly complicated solution. The peek backstage, however, makes the book well worth reading.

If the action threatened to slow down, Gypsy could always sprinkle a few professional terms into the dialogue, such as "pickle persuader," "grouch bag," and "gazeeka box."

[Gypsy believed] that any publicity was good publicity. So the creation of a "literary Gypsy" spurred her to finish her book more quickly, before the public grew tired of the idea.

Gypsy and George, no strangers to the publicity machine, had systematically amassed all the forces of book promotion to ensure its success. By winter, The G-String Murders had become the biggest-selling mystery since Dashiell Hammett's Thin Man.

Here's a long excerpt that I think shows off Lee's literary skill quite well. If this were a scene from, say, Nathanael West's The Day of the Locust undergrads would be still be puzzling over the symbolism. A Chinese waiter gives Gypsy a ginseng root, and tells her that “it only grew under the gallows where men had died,” and that “if I ate it I’d live forever.”

The girls gathered around [Gee Gee] as she broke the seals. The first one was brittle and snapped off easily. The second she had to pry off with a nail file.Two daggers out of four.

I suddenly wanted to get out of the room. My common sense told me that my fears about the box were stupid and childish, but I couldn’t help it. I was frightened. “What if there is one flower in it?” I thought. “One flower that would disappear like dust when the air hit it.” Then there would be a sickening sweet odor, bitter almonds maybe, and before we knew what happened, we would be dead.

She had removed the lead foil and held up a tin box for the curious girls to examine. The tin box was also sealed. Great chunks of brick-red wax were on either side.

I wanted to stop her, but already she had begun to lift the top. There was no flower, no needle dipped in poison, no bomb; just a cotton-lined box with two long, dried roots embedded in the fluff. The roots were tied at the top with a piece of cord.

It was by this cord that La Verne lifted the gift from the cotton. She held it for a second a watched it sway back and forth. “Look! It’s shaped like a man,” she said.

Alice shivered. “Ugh. It’th dithguthing. Put it back in the box.”

La Verne still stared at it, her green eyes wide and glistening. “Not so much like a man,” she whispered. “More like the skeleton of one.” With a cautious finger she touched the bleached, bonelike root. The pupils of her eyes dilated. She pushed the root and set it in motion again. Her heavy breathing was the only sound in the room.

Wednesday, March 12, 2014

The Gyrth Chalice Mystery (aka Look to the Lady), Margery Allingham

Margery Allingham's The Gryth Chalice Mystery (1931), marking the third appearance of Albert Campion, features the seemingly inevitable car chase in an early chapter rather than as a climax. But worry not as Campion himself ultimately rides to the rescue on horseback!

Jacques Barzun and Wendell Hartig Taylor's brief review in A Catalogue of Crime reads: "An early story with good scenes and relieved from murder by elegant robbery and clerical personages, but somewhat touched by the excessive lightheartedness of the period. Fortunately short, and thus worth an hour's inspection."

JB & WHT seem to have forgotten the death of Mrs. Dick -- which, putting Barbera's cart rather ahead of Hanna's horse, might make one think of Scooby-Doo --, and of a "clerical personage" in the novel I have no memory. Maybe, confusing scholarly with clerical, they meant the American professor?

Phillip Youngman Carter, in his preface to the short-story collection The Allingham Casebook, says the early novels "reflect the mood of the time and into them she crammed every idea, every joke and every scrap of plot which we had gathered like magpies hoarded for a year," and that is certainly the case here, so much so that the death of Mrs. Dick, once resolved is simply forgotten.

For all of its absurdities -- did someone mention Gypsies? -- The Gryth Chalice Mystery has some nice exchanges such as:

The girl looked at him incredulously. "What is that man Lugg?" she said.And here's Campion on the art of detection:

[Campion] adjusted his spectacles. "It depends how you mean," he said. "A species, definitely human, I should say, oh yes, without a doubt. Status -- none. Past -- filthy. Occupation -- my valet."

Penny laughed. I wondered if he were your keeper," she suggested.

"The process of elimination," said he oracularly [...], "combined with a modicum of common sense, will always assist us to arrive at the correct conclusion with the maximum of possible accuracy and the minimum of hard labour. Which being translated means: I guessed it."Two daggers out of four.

Friday, March 7, 2014

A Comedian Dies, Simon Brett

Detection takes a back seat to satiric commentary on the business of show in Simon Brett's fifth Charles Paris novel, A Comedian Dies (1979).

Television producers take the brunt of the skewering here while stand-up comedians and variety shows receive a rather gentler lampooning:

Paul Royce looked petulant. "I thought the idea of this show was to try out something new, to bring you up to date."

"Try out something new, yes. But I'm still Lennie Barber. It's got to be new material, but new Lennie Barber material. I haven't spent a lifetime building up my own comic identity to have it thrown over like this. Listen, that sketch might go all right in Monty Python or whatever it's called--"

"Oh, so you don't think Monty Python's funny?" asked Paul Royce, leading Barber into a pit of impossibly reactionary depths."As usual with the Charles Paris series, once a dead body finally hits the ground what had been a breezy, gossipy entertainment becomes more of a forced march to a solution. In A Comedian Dies, Paris's skill as a detective matches his lack of success as an actor as he accuses nearly every other character of being the murderer and never does get it right.

Paris also never does bring to justice a character who doles out an horrific beating in what turns out to be a red herring. It's almost as though Brett added the description of the aftermath of the beating to placate a publisher calling for more violence in the book.

Two daggers out of four.

[Note: Just learned that this March 8 marks the 37th anniversary of the transmission of the first radio episode of "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" written by Douglas Adams and produced by none other than Simon Brett.]

Wednesday, March 5, 2014

Murder in the Ball Park, Robert Goldsborough

Murder in the Ball Park (2014), Robert Goldsborough's ninth Nero Wolfe mystery since the Stout estate gave him the keys to the franchise in 1986, fails on every level.

Most unsatisfactory.

Zero daggers out of four.

Monday, March 3, 2014

Strong Poison, Dorothy Sayers

Lord Peter Wimsey makes his fifth novel-length appearance in Dorothy Sayers' Strong Poison (1930). Having read (1) the series out of order and having read the eleventh book -- Busman's Honeymoon (1937) -- most recently, it came as something of a shock to find Wimsey's confederate Miss Climpson hanging the jury trying Wimsey's beloved Harriet Vane for the arsenic poisoning of her former lover (2). As it turns out, of course, Vane and Wimsey are only just beginning their long courtship.

Even though Sayers was only 37 when Strong Poison was published, she reveals an interesting concern about growing older. At one point, Wimsey says

"Give me good food and a little air to breathe and I will caper, goat-like, to a dishonourable old age. People will point me out, as I creep, bald and yellow and supported by discreet corsetry, into the night-clubs of my great-grandchildren, and they'll say, 'Look, darling! that's the wicked Lord Peter, celebrated for never having spoken a reasonable word for the last ninety-six years. He was the only aristocrat who escaped the guillotine in the revolution of 1960."At another point, the omniscient narrator says, "when [Wimsey] was an old man," which begs the question: From whence is Strong Poison being narrated?

I suppose Sayers was trying to distance herself from her time, which as this scene from a Bohemian musical performance illustrates, Sayers found rather silly:

"Bah!" said a voice in Wimsey's ear, as the cadaverous man turned away, "it is nothing. Bourgeois music. Programme music. Pretty! -— You should hear Vrilovitch's 'Ecstasy on the letter Z.' That is pure vibration with no antiquated pattern in it. Stanislas -— he thinks much of himself, but it is old as the hills —- you can sense the resolution at the back of all his discords. Mere harmony in camouflage. Nothing in it. But he takes them all in because he has red hair and reveals his bony structure."Strong Poison features Miss Climpson perhaps a little too much -- though her Ouija board endeavors are amusing (and certainly seem to have inspired Patricia Wentworth's 1941 Weekend With Death, reviewed below) -- but moves along a quite a brisk pace and sets the scene for better books to follow, i.e. Gaudy Night.

Three daggers out of four.

(1) Counting here having listened to the audiobook of The Five Red Herrings as having "read" it.

(2) As much as a plot-summary as I intend to do in the reviews on this blog.

Wednesday, February 26, 2014

A Pocket Full of Rye, Agatha Christie

Agatha Christie's A Pocket Full of Rye (1953) features Miss Marple (though she doesn't make her first appearance until nearly half-way through) in a novel for the sixth time.

As Vanessa Wagstaff and Stephen Poole say in Agatha Christie: A Reader's Companion "[Miss Marple] quickly forges a highly effective partnership with the unusually receptive and astute Inspector Nelle, who later assists Poirot in Third Girl (1966)."

Wagstaff and Poole also call A Pocket Full of Rye "one of Christie's best novels, with all the classic ingredients of a Miss Marple murder...."

On the other hand, Jacques Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor in A Catalogue of Crime say, "Rather tired Christie. Miss Marple officiates. The murder is of a gent in an office, by poison. The scene is full of housemaids and annoying indirections by Miss Marple."

Where JB and/or WHT fail to mention the two murders which follow the gent's in his office Wagstaff and Poole seem rather comically easy to please.

A Pocket Full of Rye notably shows Christie questioning the Golden Age's Taylorian obsession with time management. A character says, "One doesn't look at clocks the whole time."

I don't have any evidence to show that Christie ever read Marie Rodel's Mystery Fiction: Theory and Technique (1952) in which she says, "Insofar as the rules of the game are concerned, an insane murderer represents cheating on the author's part, because the reader cannot be expected to figure out for himself the murderer's mental processes," but Christie seems as though she has taken the lesson to heart. Inspector Neele says, "I'm going by sober facts and common sense and the reasons for which sane people do murders."

Certainly not a bad book but sloppily put together -- characters and red herrings are introduced but are often allowed to simply slip away. Rather like the case of the four-and-twenty blackbirds, A Pocket Full of Rye feels half-baked.

One dagger out of four.

Monday, February 17, 2014

Mystery Mile, Margery Allingham

Margery Allingham's Mystery Mile (1930) features Albert Campion in his first starring role, after having appeared in a supporting role in the previous year's The Crime at Black Dudley (see review below).

Campion exaggerates his importance in the foregoing case, though, saying "That's the Black Dudley dagger.... An old boy I met was stuck in the back with that, and everyone thought I'd done the sticking. Not such fun."

Allingham presents Campion as more than an amateur detective, less than a mercenary, and not quite a crook. And, throughout, Campion disguises his keen intelligence with nearly non-stop patter:

"What a gastronomic failure the British Burglar is," he remarked, reappearing. "A tin of herrings, half a Dutch cheese, some patent bread for reducing the figure, and several bottles of stout. Still better than nothing.... The whisky's there, too, and there's a box of biscuits somewhere. Night scene in Mayfair flat -- four herring addicts, addicting."As B.A. Pike points out in Campion's Career: A Study of the Novels of Margery Allingham, the chief distinction of Mystery Mile is that it introduces Campion's gentleman's gentleman Lugg:

Lugg is first brought to our notice as a "thick and totally unexpected voice" on the telephone, huskily announcing himself as "Aphrodite Glue Works".... His actual appearance is delayed until ... he is revealed as "the largest and most lugubrious individual ... a hillock of a man, with a big pallid face which reminded one of a bull-terrier...." His criminal antecedents are delicately hinted at -- he wears "what looked remarkably like a convict's tunic" -- and the special nature of his relation with Campion -- mutual derision veiling the deepest affection and trust -- is defined in the first of many entertaining dialogues.Late in Mystery Mile, the villain, the head of a secret criminal cabal, reveals that Campion had been "once commissioned by us on a rather delicate mission in an affair at a house called Black Dudley." Allingham, however, lets this revelation waft off in the breeze and moves merrily along to the conclusion of the case at hand.

If nothing else, Allingham keeps these early Campion books moving along. One gets the sense that she is making them up as she goes along, often losing her way. For instance, once gangsters kidnap a female character the search for Mystery Mile's original missing person falls by the wayside, seemingly forgotten by all.

Phillip Youngman Carter, in his preface to the short-story collection The Allingham Casebook, says the early novels "reflect the mood of the time and into them she crammed every idea, every joke and every scrap of plot which we had gathered like magpies hoarded for a year."

Inconsequential, silly fun.

Two daggers out of four.

Friday, February 14, 2014

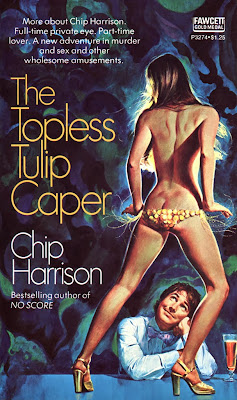

The Topless Tulip Case, Lawrence Block

With the fourth, and final, Chip Harrison novel, The Topless Tulip Caper (1975) Lawrence Block pulls off a very entertaining Nero Wolfe pastiche. Chip Harrison makes a very satisfactory Archie Goodwin and Block provides a satisfactory Nero Wolfe in Leo Haig.

In an interview with Ethan Iverson on Do the Math, Block explains:

Set for the most part in a strip club called the Treasure Chest, one would think that that would be sex enough for any reader but as Block writes in his memoir, Afterthoughts:

In an interview with Ethan Iverson on Do the Math, Block explains:

The first two [Chip Harrison books], of course, are sort of young man coming of age novels, and the only way they could be a series was if he changed somewhat, because you couldn’t have the same person coming of age forever. So, I put him to work for a Nero Wolfe wannabe and that was fun. But again, it was essentially a one trick pony, and two books and a couple of short stories was plenty.David Vineyard, in "Fifty Funny Felonies + Fifty More" on Mystery*File says, The Topless Tulip Caper "is also cheerfully dirty minded without a smirk or a snicker -- a rarity in any American fiction."

Set for the most part in a strip club called the Treasure Chest, one would think that that would be sex enough for any reader but as Block writes in his memoir, Afterthoughts:

Joe Elder, whom I'd known back in the Scott Meredith days, was Chip's editor. At some point after he'd agreed to publish Make Out With Murder, I went in to meet Joe, who hadn't know who was lurking behind Chip Harrison's name.Four daggers out of four.

He agreed that a fourth book would work out all right, and I went home to write it. I'd already made Haig an avid aquarist, with tropical fish serving him as orchids served Nero Wolfe. And, happily enough, I knew something about tropical fish.

When I delivered the book, Joe had a complaint I'd rarely heard in many years in the world of paperback fiction.

"There's not enough sex," he said.

In response, I went through the book page by page until I could find a place where I could wedge in a sex scene. And Chip, after recounting it in some detail, apologizes for it as having not much to do with the book; he explains that his editor, Joe Elder, insisted he augment the book's sexual content. So, although the incident really did take place, Chip thinks it's gratituous, and rather hopes Mr. Elder will change his mind and take it out again.

Sunday, February 9, 2014

The Case of the Crumpled Knave, Anthony Boucher

The supremely silly The Case of the Crumpled Knave (1939) is Anthony Boucher's second mystery novel and the first of four to feature Fergus O'Breen. William F. Nolan, writing on MysteryNet.com says, O'Breen "was conceived as a kind of West Coast Ellery Queen with an Irish brogue."

Throughout the novel Boucher breaks the fourth-wall with characters commenting on the fact that they are characters in a book. Boucher, who is probably best known as an editor and critic, is also not adverse to dropping the names of other writers:

"As a private investigator," Fergus answered as they settled into a booth, "I'm as unorthodox as hell. Mr. Latimer [creator of Bill Crane, the drunk detective] wouldn't approve of me one little bit. I rarely drink on a case at all, and never before lunch."

"You got it all wrong... There's no John Dickson Carr touch to this -- no locked room problem at all. In a way I'm sorry. I've always wondered if those things happened in real life...."

This department isn't afraid to call in reinforcements to do the heavy lifting so here's Will Cuppy commenting on The Case of the Crumpled Knave in the April 16, 1939, edition of the New York Herald Tribune Books:

"Sure enough, Mr. Garnett is soon lifeless (prussic acid) beside a jack of diamonds.... Mr. Garnett was a collector of playing cards, much interested in the more scholarly and abstract aspects of same. He was much given to muttering, 'Which is the true symbol of life -- chess or cards?' and such things. (Chess probably is, if you call that life.)"

I was thrilled to find that the public library had a copy of the original Simon & Schuster hardcover. Nice to know that The Case of the Crumpled Knave has gotten checked out often enough to avoid the dreaded cull.

Two daggers out of four.

Thursday, February 6, 2014

Murder on the Blackboard, Stuart Palmer

Murder on the Blackboard (1932) by Stuart Palmer features schoolteacher Hildegarde Withers and police inspector Oscar Piper for the third time.

As one of the characters jokes, "Schoolteachers rush in where detectives fear to tread, or something."

Murder on the Blackboard abounds with humor as well as the clues (and red herrings) necessary for a satisfactory mystery novel.

Palmer's sense of humor is well-illustrated by these two quotes:

"Then [Miss Withers, who was reading the letters section of the newspaper,] returned to Irate Citizen, who was openly in favor of legible house numbers and against dry-sweeping."

"Anderson was letting the words tumble forth, like a pent-up torrent. 'I play the stock market, I lose. I play the Mexican lottery, I lose. I play the Chinese lottery, I lose, again and again. I bet on Dempsey in Philadelphia, and on Al Smith in the election. Always I lose.'"

"Anderson was letting the words tumble forth, like a pent-up torrent. 'I play the stock market, I lose. I play the Mexican lottery, I lose. I play the Chinese lottery, I lose, again and again. I bet on Dempsey in Philadelphia, and on Al Smith in the election. Always I lose.'"And who says mystery novels aren't educational? I learned that a cane like this is called a "whangee." Who knew?

I found my International Polygonics reissue of Murder on the Blackboard for only 75 cents plus postage. All Palmer's other books, however, are going for much more than that bargain price!

Three-and-three-quarter daggers out of four.

Monday, February 3, 2014

The Crime at Black Dudley, Margery Allingham

Margery Allingham's The Crime at Black Dudley (1929) marks the introductory appearance of Albert Campion, who would feature in 18 future novels.

And quite an introduction it is:

"That's a lunatic.... His name is Albert Campion," she said. "He came down in Anne Edgeware's car, and the first thing he did when he was introduced to me was to show me a conjuring trick a two-headed penny -- he's quite inoffensive, just a silly ass."

Campion figures heavily in one plot thread -- involving a group of Bright Young Things being held captive in a country manor filled with secret passages -- but plays no role in the solution of a secondary murder mystery.

Those expecting a sedate country house locked room puzzle should look elsewhere. (The degree of seriousness with which The Crime at Black Dudley was written is indicated by the name of the villain: Eberhard von Faber!)

Phillip Youngman Carter, in his preface to the short-story collection The Allingham Casebook, says the early novels "reflect the mood of the time and into them she crammed every idea, every joke and every scrap of plot which we had gathered like magpies hoarded for a year."

Two daggers out of four.

Friday, January 31, 2014

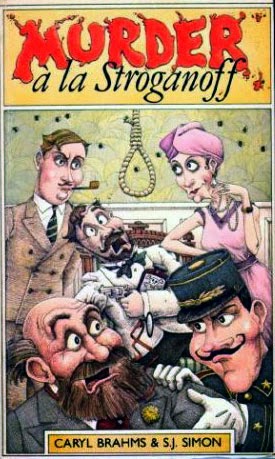

Murder à la Stroganoff, Caryl Brahms and S.J. Simon

Caryl Brahms and S.J. Simon's Murder à la Stroganoff (1938; U.K. title Casino for Sale) is the second of three novels to feature the Ballet Stroganoff and inspector Quill, late of Scotland Yard.

Malcom J. Turnbull in “Inspector Quill: Sleuthing in the Ballet and the Balkans” quotes Jane W. Stedman, “It is likely... that readers of these works find less pleasure in clues and unravelment than in the ebullient collusion of fantastically comic characters.”

Turnbull continues, “Certainly the authors persistently subordinate puzzle and sleuthing to humour, yet all three books contain orthodox whodunit properties and conform in a number of regards to classic and Golden Age norms. Brahms and Simon offer readers the obligatory corpses, circles of suspects (all with motives for mayhem), recountings of the investigation process, and climactic revelations of the culprits’ identities.”

Brahms and Simon even poke a little fun at those classic norms, "Quill sighed. Here he was at last presented with one of those cases with all the doors and windows locked which every hard-pushed author resorts to sooner or later."

Brahms and Simon have a great time with characters such as impresario Vladimir Stroganoff, who seems to have succeeded in spite of his efforts, and Quill, who succeeds because of his hard work and in spite of obstacles continually thrown in his path.

Stroganoff speaks in tortured English with a soupçon -- rather a large soupçon, actually -- of French phrases tossed in: "To call the police tout de suite it is not wise. They will ask the question, they will learn that it is I who see Citrolo last and then I will be in prison. At all costs, I say, I must prevent that. The Ballet Stroganoff it need me too much."

Brahms and Simon proceed from the premise that if a joke is funny the first time it will be even funnier the third or fifth time.

Towards the end of the book, as various plot threads begin to come together, I was reminded of John Kennedy Toole’s Confederacy of Dunces. It wouldn’t be a surprise if Toole has a Brahms & Simon fan.

I bought a Polygonics International, Ltd. reprint via Half.com for 75 cents plus shipping.

Three-and-a-half daggers out of four.

Monday, January 27, 2014

Weekend With Death, Patricia Wentworth

Weekend With Death (1941) by Patricia Wentworth is her penultimate stand-alone mystery novel. Silence in Court (1945) was her final stand-alone but she wrote 29 more Miss Silvers novels before her death in 1961.

Weekend With Death is more of a spy thriller with an unwilling civilian protagonist that a cozy whodunit. Wentworth supplies the novel with an interesting cast of characters, especially a pair of paranormal investigating siblings, but the plot has appalling logical gaffes.

Still, Wentworth creates a great deal of suspense and manages to pull off a couple of nifty surprises (though it could be argued that she doesn't completely play fair).

As Weekend With Death was published during World War II, it seems strange that the bad guys are only obliquely identified as Germans until Hitler's name is finally mentioned in the book's final pages. Not an especially rousing book for propaganda purposes. Were Wentworth and the publishers, J.B. Lippincott in the U.S. and in the U.K., under the title Unlawful Occasions, Lythway Press, hedging their bets? Seems unlikely, but the question begs for further research.

Taking a cue from Past Offences blog, I'm going to start mentioning where I found the book under review and how much I paid for it. Weekend With Death was a bargain at just a quarter from the University City Public Library book sale. Considering that prices on-line range from $60 for a vintage paperback (see below) to $750 for the hardcover first edition I'd say I got quite a deal. My first edition hardcover has some bent pages in the middle, lacks a dust cover (see above), and has a loose spine so it's not a particularly prime specimen.

Two-and-a-half daggers out of four.

Thursday, January 23, 2014

The White Priory Murders, Carter Dickson

The White Priory Murders (1934) by Carter Dickson (a pseudonym of John Dickson Carr) is the second novel to feature Sir Henry Merrivale.

Unfortunately, it's overly talky and fails to live up to the potential promised by the clash of cultures as Hollywood meets British academia.

Jacques Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor's review in A Catalogue of Crime (1971) says it best:

"Sir Henry Merrivale is caught up in the murder of a wilful actress; it's done inside a pavilion, snow is on the ground, and there are crowds of candidates for her favors and for the role of murderer. ... The telling is done in Carter Dickson's usual long and diffuse talk which he thinks conversation; oddities are added for pseudo suspense; people shout, whirl, say "What!" in italics, and generally the thing is irritation unrelieved even by a second murder."

Merrivale is an entertaining character but after a brief appearance in the early pages doesn't return until the last quarter of the book. My theory that he owes more than a little to Rex Stout is bolstered by Merrivale saying not only "flummery" but also "phooey," in the Archie Goodwin spelling, though, rather than Nero Wolfe's "pfui." [A theory not borne out by facts, however. See comments section.]

Dickson has Merrivale point out early on that another character is "talkin' like a fool detective in a play. This is real. This is true." Later on, he says, "I must 'uv read a dozen stories like that, and they were funnier than watchin' somebody sit on a silk hat."

One-and-a-half daggers out of four.

Sunday, January 19, 2014

Dancers In Mourning, Margery Allingham

Dancers in Mourning (1937), Margery Allingham's 9th Albert Campion novel, is not, as described in the blurb in the Crime & Mr. Campion omnibus, a "novel about the world of the ballet."

The titular dancers, rather, are of the musical revue sort, and the first third of the novel functions as something of a satire of the genre, as well as providing the template for Simon Brett's Charles Paris series.

Dancers in Mourning loses narrative steam in the second half as a suicide becomes more and more obviously a murder and the novel moves from backstage intrigue to a police procedural set in a country manor.

As a premonition of the coming war, Allingham shakes up the proceedings with a truly unexpected murder by grenade. And if three deaths weren't enough, Allingham adds a brutal bludgeoning by spanner.

Lugg appears only briefly but manages to say this about Campion:

"Got yourself mixed up in a suicide now, I see. People lay themselves open to somethink when they ask you down for a week-end, don't they? 'E's a 'arbinger of catastrophe."

In addition to trying to solve the murders, Campion also must come face to face with a moral dilemma. As a police inspector comments, "Right's right and wrong's wrong. He knows that."

Three-and-a-half daggers out of four.

Saturday, January 11, 2014

Flowers for the Judge, Margery Allingham

Flowers for the Judge (1936) is Margery Allingham's 7th novel to feature amateur detective Albert Campion.

Combining not only a locked room mystery but also a 20-year-old missing person case with courtroom drama, Flowers for the Judge is a delight.

Campion, and his gentleman's gentleman Lugg, are something of a parody of Dorothy L. Sayers' Lord Peter Wimsey and Bunter, but for all of Flower for the Judge's humor it is serious and ultimately more than a little moving.

I hope I'm not spoiling anything by suggesting that a better title might have been Tears of a Clown.

Flowers for the Judge's publishing-firm setting gives Allingham a chance to comment on her own chosen vocation:

"Mr. Campion, who thought privately that all young persons who voluntarily shut themselves up half their lives alone, scribbling down lies in the pathetic hope of entertaining or instructing their fellows, must necessarily be the victims of some sort of phobia, was duly sympathetic."Four daggers out of four.

Monday, January 6, 2014

The Four False Weapons, John Dickson Carr

The Four False Weapons (1937) is the last of five novels to feature John Dickson Carr's French sleuth Monsieur Bencolin.

Fairly run-of-the-mill locked room puzzle enlivened by a totally unexpected high-stakes card game.

It takes Carr until very late in the book to make the de rigueur for the era joke that one of the characters "worked out this plot with a loving ingenuity, exactly in the style of his favorite detective fiction."

Will Cuppy, in his "Mystery and Adventure" column in the New York Herald Tribune Books on October 10, 1937, said:

"Just as [one of the characters] is unjustly accused on the murder, who should arrive but Henri Bencolin, the greatest detective in France, who has been milling around in an old corduroy coat for just such an entrance. The return of Bencolin, indeed, after an absence of some seasons is the talking point of this complicated and exciting yarn."

Two daggers out of four.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)